Test Policy

This is a work-in-progress guide on the testing policy for the Online Trade Tariff. This document defines what testing should be done and how.

What is the point of testing?

There are many reasons why we should test our code, but practically speaking, the most important reason is to ensure that our code works as expected. Testing, whether it’s manual or automated, is a way of giving us confidence that our code is working as we expect it to, and will continue to work as we expect it to.

Well tested code is easier to maintain, easier to extend, and easier to deploy.

This policy strives to form a baseline for what we should be testing and how. Principally this is in order to ensure we keep our test suite in line with the values of keeping things simple and necessary. Test suites should be fast razor sharp tools for instilling confidence, not a wall we have to climb over to move forwards.

What should we test?

- Core functionality that is critical to the system. We must know that once implemented, this functionality will continue to work as expected through later change and refactoring

- Areas of doubt. If we are not 100% sure that a particular area of code is correct, we should test it to make sure we know that it is correct.

Adding tests for code we are confident in arguably adds technical debt to the codebase. These are tests that slow down the test suite for little benefit, and add brittleness to the codebase through change. Think carefully about whether this is a good trade-off before adding tests. Think - are your tests necessary?

What should we not test?

- We do not need to test code which is part of other components (e.g Rails). We do not need to test

validates_uniqueness_ofworks as this is tested extensively in the Rails test suite.

When should we test?

Ideally we should test as soon as we write code. However, we should also test as we go, and we should test in a way that makes it easy to do so. We should aim to test our code as soon as we can, but we should also aim to test it as late as possible. Principally, tests are a way of giving us confidence that our code is correct. If we are merging a PR or deploying a release, all tests should always be run and always be passing. If we have even a single failing test, we should not deploy/merge.

How do we test?

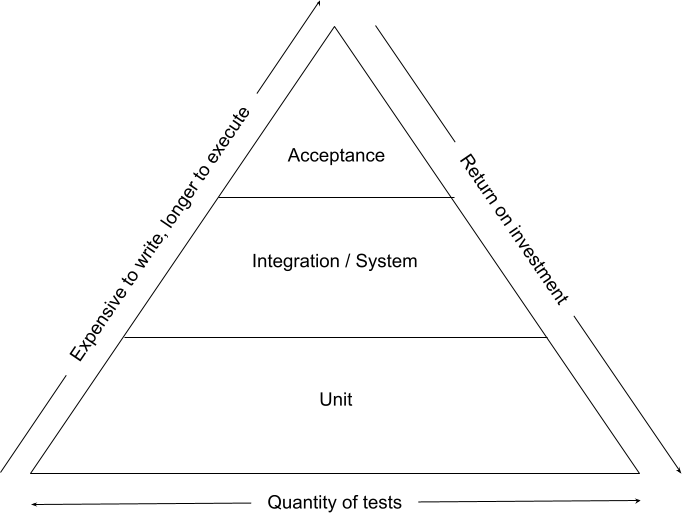

There are principally three types of testing we should be doing:

- Unit tests

- Integration tests

- Acceptance tests

Unit tests

Unit tests are tests that test a single unit of code. These tests should be fast, and should not require any external dependencies. They should be written in a way that makes them easy to run and easy to understand. These tests are designed to be run quickly, and to give us confidence that a specific unit of code is working as we expect it to. Ideally these tests should be run on every code change via local CI tools such as Guard.

Unit tests are primarily aimed at units which contain complex logic e.g. models, services, libraries etc.

Unit tests are written using RSpec. The RSpec documentation is a good place to start.

Integration/System tests

Integration tests are tests that test the interaction between multiple units of code. These tests may be slower, and may require external dependencies. Typically these tests are designed to test a ‘slice’ of the system, e.g. a single request on the API, or a single page on the website. Again, these tests should be ideally run on every code change via local CI tools.

Integration tests are written mostly using RSpec. However the type of test may require different tools. For example, an API request spec may be written using RSpec, whereas a page spec may be written using Capybara.

Acceptance tests

Acceptance tests are the tests that prove the system as a whole works as we expect it to. These tests are designed to test the principle user journeys through the system. They should not get into the details of an implementation (i.e. specific text in a paragraph for instance), but should prove that the user can carry out the task they are trying to do successfully. Acceptance tests act as the final verification of the required business functionality and proper functioning of the system, emulating real-world usage conditions on behalf of the customer.

Acceptance tests are nearly always written using Capybara. The Capybara documentation is a good place to start.

Notes

Synthetic testing

Synthetic tests are tests that are not designed to test a specific unit of code, but rather to test the behaviour of the system as a whole. Many acceptance tests can be used as synthetic tests, however synthetic tests are typically run in a production environment on a regular basis. These tests are built to test common user journeys through the system in a way that will not change the system state in any way - for instance: Can a user log in? Can they carry out a search?

Where possible, acceptance tests should be used as the basis for synthetic tests, either partially or fully. For example, if we have an acceptance test that tests the ability of a user to search for a document, we could potentially re-purpose or re-use that test in a synthetic context.

JavaScript testing

JavaScript is a dynamic language, and as such, it is difficult to test. There is an abundance of JavaScript testing frameworks, but they are not all equally good. What’s more JavaScript testing is often done in JavaScript itself, which is not ideal due to the differing language and frameworks to the rest of the test suites we might be managing.

Therefore, where possible, we should aim to test JavaScript using the same tools we already use, such as Capybara. This will provide us with a commonality across our test suite and also allow us to use familiar tools in a more obvious way. For instance:

Jasmine:

$("#someButtonId").trigger("click");

expect('click').toHaveBeenTriggeredOn('#someButtonId');

menu = $('#menu').attr('class');

expect(menu).toBe('menu-visible');

vs Capybara:

click_on('Menu')

expect(find("#menu").visible?).to be true